S01E12: Queen ❌ Duchess ✅ of Crime: Ngaio Marsh

Why is this grand dame of golden age mystery largely forgotten today?

As I sit down to face this blank Substack page, I grapple with an unusual challenge—writing about an author who is not on my favourites list.

Then why write about her at all?

This is the kind of inner crisis I wrestle with when, at a house party, someone puts a bowl of plain salted Lays in front of me. Taking chip after chip, I find myself thinking: why am I eating this? Yes, it’s deliciously salty and crispy but I don’t love it. Shouldn’t I save my cheat-calories for the snack I love best? Then again, this is so damn salty in an absolutely finger-licking, lip-smacking way… and so on and so forth until the bowl is empty.

That is a laboured metaphor for my relationship with the works of Dame Ngaio Marsh, a New Zealand writer who achieved great popularity in her time. She was hailed alongside Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, and Margery Allingham as a ‘Queen of Crime’. In 1949, Penguin and Collins released a million copies of her works on the same day—and all of them got sold.

Ngaio1 was actively writing into the 1970s and 80s. Yet, her fame never endured like Agatha Christie’s (nearly 50 years after whose death, her popularity is still being milked by the likes of Sophie Hannah and Kenneth Branagh). Nor have Ngaio’s works seen a sudden revival of interest like those of Josephine Tey or E.C.R. Lorac. That said, she never went out of print and continues to have a devoted following.

In this, the twelfth episode2 of About Murder, She Wrote., let me tell you why Ngaio Marsh is both brilliant and frustrating.

A Lady of Many Talents

Ngaio (pronounced nye-oh; a name with Maori origins) was born in Christchurch, New Zealand in 1895. She trained as an artist and was the founding member of The Group, an artists’ community, many of whose members would go on to be famous.

While in college, she became interested in theatre and began writing, acting, and later, producing plays. In fact, she is credited with single-handedly reviving Shakespearean theatre in New Zealand.

In the 1920s, she travelled to England and began writing syndicated travel articles under the pseudonym ‘A new Canterbury pilgrim’. With a friend, she also set up an interior decor shop in London, called Touch and Go.

In short, she was a polymath or multipotentialite long before LinkedIn lunatics made these terms embarrassing. Later, these life experiences made their way into her novels and helped bring them alive.

Class, Race and Other English Influences

It was while living in London and running her shop that Ngaio wrote her first novel. Here is the origin story in her own words.

All day, rain splashed up from the feet of passers-by going to and fro, at eye level, outside my water-streaked windows. It fanned out from under the tyres of cars, cascaded down the steps to my door and flooded the area. ‘Remorseless’ was the word for it and its sound was, beyond all expression, dreary. […]

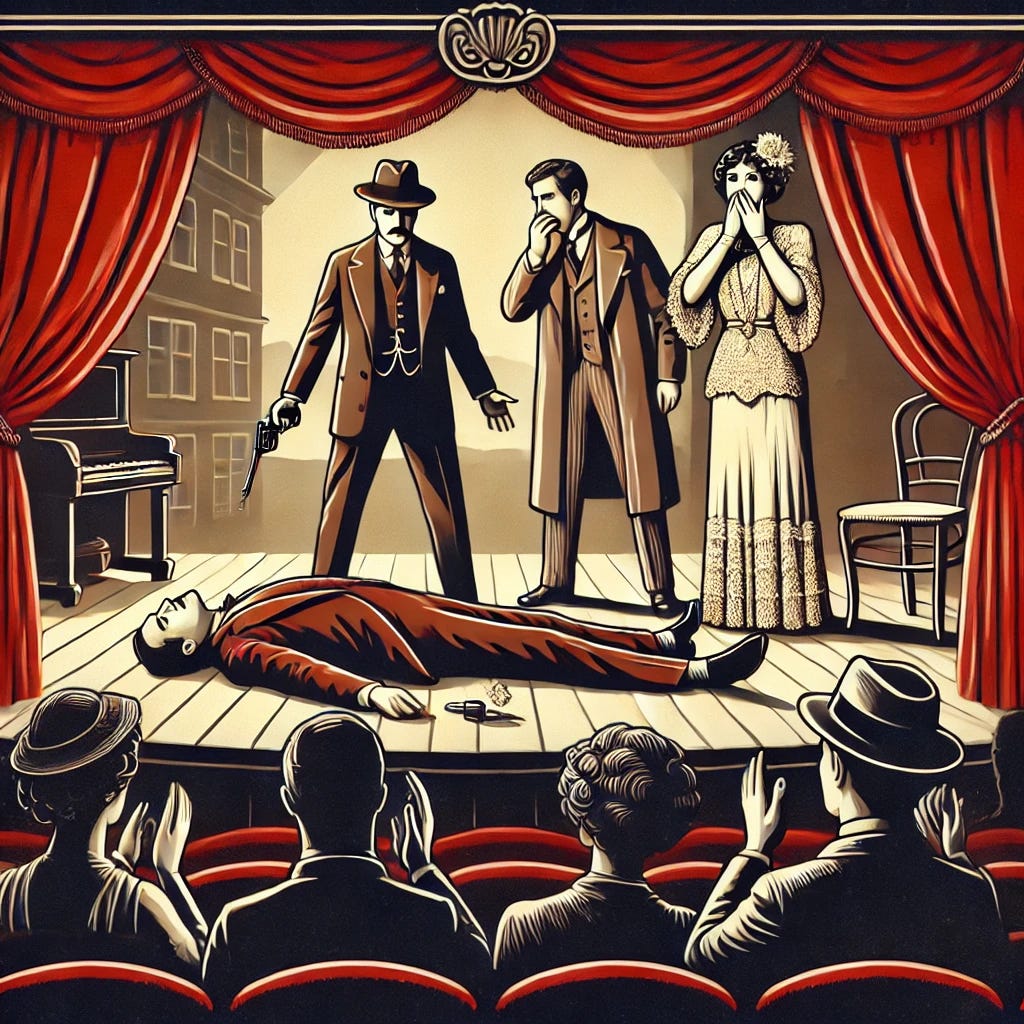

I read a detective story borrowed from a dim little lending library in a stationer’s shop across the way. Either a Christie or a Sayers, I think it was. By four o’clock, when the afternoon was already darkening, I had finished it, and still the rain came down. I remember that I made up the London coal fire of those days and looked down at it, idly wondering if I had it in me to write something in the genre. That was the season, in England, when the Murder Game was popular at weekend parties. Someone was slipped a card saying he or she was the ‘murderer’. He or she then chose a moment to select a ‘victim’, and there was a subsequent ‘trial’. I thought it might be an idea for a whodunit – they were already called that – if a real corpse was found instead of a phony one.

I played about with this idea. I tinkered with the fire and with an emergent character who might have been engendered in its sulky entrails: a solver of crimes.

The room had grown quite dark when I pulled on a mackintosh, took an umbrella, plunged up the basement steps and beat my way through rain-fractured lamplight to the stationer’s shop. It smelt of damp news-print, cheap magazines, and wet people. I bought six exercise books, a pencil and pencil sharpener and splashed back to the flat.

Then with an odd sensation of giving myself some sort of treat, I thought more specifically about the character who already had begun to take shape.

As you can see, she was an excellent creator of settings. The book she wrote was a classic country house mystery A Man Lay Dead. In a career spanning fifty years, she wrote 32 novels, most of which are set in England. Only four are set in New Zealand, although it can be argued that those are among her best works.

While she was a New Zealander all her life, Ngaio was raised in an anglophilic, class-conscious society. Her mother was born in NZ to Englishpeople who had migrated there in the 1850s. Her father had moved there from England as a bank clerk.

Christchurch was a place that had been imbued with a strong sense of class and position right from its beginnings, when in 1850, four shiploads of settlers under the auspices of the Church of England arrived from Britain to expand the town. The passengers on these ships had been specially selected so that they represented the “proper balance squire, merchant, artisan and labourer” according to a 1980s history of the city. Basically, the aim was to export the British class system to this part of New Zealand as a way of getting away from the idea, common at the time, that emigration could be a way of making a fortune and escaping from social structures. (Source: Shedunnit)

Traces of this upbringing are evident in many of her works. For instance, take the “solver of crimes” she created: Inspector Roderick Alleyn. While her contemporaries favoured the skilled amateur detective (Hercule Poirot, Albert Campion, Lord Peter Wimsey, Roger Sheringham, et al), Ngaio chose a career policeman. However, she couldn’t help writing him as a gentleman detective.

He is handsome, Oxford-educated, the younger son of a baronet, a WWI veteran, and ex-British Foreign Service. When we meet him for the first time, Alleyn is already Detective Chief Inspector in the Scotland Yard CID. Though he rarely flaunts it, this background gives him a clear advantage when dealing with suspects from the upper classes who treat him as an equal and not an outsider.

However, while some of her writings are stuck in their time, Ngaio was never xenophobic or racist like many of her contemporaries. Her Maori and African American characters (their existence itself is unusual) are created with respect and don’t come across as caricatures, although they do suffer from an otherness born out of being seen through an English lens.

A Writer of Brilliant First Halves

Ngaio did three things incredibly well, typically in the first half of her novels.

Create diverse and interesting settings: the backdrops for her novels range from a strange religious cult to a travelling theatre group, a jazz band, a sheep farm, an artists’ colony, New Zealand’s hot springs, and more, in addition to the usual assortment of English country houses and parties.

Sketch memorable characters: If Agatha Christie could make us imagine what a character is like with a few carefully worded phrases, Ngaio Marsh has the gift of showing us exactly what someone is like through sharp, vivid descriptions and glimpses into their minds.

Write with wit and humour: Ngaio’s descriptions are often hilarious, occasionally teetering on the verge of cruel accuracy.

Beneath it hung a faded photograph in an Oxford frame. It presented a Victorian gentleman wearing an ineffable air of hauteur and a costume which suggested that he had begun to dress up as Mr. Sherlock Holmes but, suddenly losing interest, had gone out fishing instead. (Death and the Dancing Footman)

The coroner summed up at considerably length and with commendable simplicity. His manner suggested that the jury as a whole was certifiable as mentally unsound, but that he knew his duty and would perform it in the teeth of stupidity. (Death at a Bar)

An example of a character in Colour Scheme, writing a letter that reveals more about him than any description could.

Dear Forster (he wrote),

Many thanks for your letter. It requires a frank answer and I give it for what it’s worth. Wai-ata-tapu… is the property of my sister and her husband, who run it as a thermal spa. In many ways, they are perfect fools, but they are honest fools and that is more than one can say of most people engaged in similar pursuits… Perhaps it is unnecessary to add that they make no money and work like bewildered horses at an occupation that requires the mere application of common sense… As for your spectacular patient, I don't know to what degree of comfort he is used, but can promise him he won't get it, though enormous and misguided efforts will be made to accommodate him.

Inspector Alleyn himself has a dry, ironic humour and a self-deprecatory manner of speaking that mocks while paying tribute. In Overture to Death, he deduces that a witness is part of a local theatre group without asking any questions.

“Hullo!" Dr. Templett took his pipe out of his mouth and stared at Alleyn. "Now, did any one tell you that, or is this the real stuff?"

"I'm afraid it's not even up to Form I at Hendon. [said Alleyn] There's a trace of grease paint in your hair. I wish I could add that I have written a short monograph on grease paint."

This is a tongue-in-cheek reference to the many monographs of Sherlock Holmes.

Where Ngaio Makes Me Go Aiyyo*

This is the anatomy of a typical Ngaio novel. The first half is absolutely brilliant. The last quarter is solid, if not exceptional. Sadly3, there’s also a middle.

In most murder mysteries, things get exciting once the detective appears on the scene. The opposite happens in Ngaio’s case. Alleyn’s detective work is rather humdrum. There are lengthy interviews of suspect after suspect and Alleyn’s team reports on various pieces of evidence or test results.

There’s a final examination of the crime scene, sometimes a re-construction of the crime, and then the denouement. Unlike Hercule Poirot, Alleyn doesn’t do any living room theatrics. Unlike Lord Peter Wimsey, he doesn’t go through any inner turmoil. All of which make him a solid real-life policeman but a fairly boring fictional detective.

My favourite mystery blogger Brad describes Ngaio’s saggy middle as “dragging the Marsh”. Confession: I skim the marsh with only a small amount of guilt.

Ngaio’s solutions don’t have the magic of John Dickson Carr’s conjuring tricks or the breathless payoff of Agatha Christie’s shocking twists but they are rarely ridiculous or implausible. Which is why her books are consistently rated six or seven on ten. There are no perfect tens but there are few ones either (looking at you: Passenger to Frankfurt).

I believe I have discovered what frustrates me about Ngaio Marsh. It isn’t that she is not a good writer. It is that she comes so close to greatness, time and again, but never reaches it.

Read her for the wonderful characters, the humour, the interesting settings, and the reliable solidity of her plots and keep modest expectations about the puzzle element. You won’t be disappointed.

Show of the Week

I have long rued the fact that we can’t access Acorn TV or BritBox in India—but in mid-2024, I discovered that we can subscribe to BBC Player via Amazon Prime. For an annual fee of ₹599, you can access a small but growing collection of BBC mystery, drama, comedy and documentaries. It’s certainly keeping me from a life of piracy crime.

Shakespeare & Hathaway is one of the first shows we binged on BBC Player. At first glance, the series gives off Hallmark movie vibes, but don’t be put off. It builds up steam in the second episode and really comes into its own by the fourth or fifth. The main characters are immensely likeable: Frank Hathaway, an ex-cop turned PI; Luella Shakespeare, former hairdresser, new PI; and Sebastian, their RADA-graduate receptionist who's a master of disguises.

Every episode is a standalone mystery that is well-clued, punctuated with Shakespearean word play, and balancing human drama with puzzle solving. Bonus: it’s set in Stratford-upon-Avon, the birthplace of the Bard, so you can enjoy picturesque views of the Cotswolds. I visited this part of the world in 2019 and my jaw was permanently a-drop.

Rating: 🩸🩸🩸🩸🩸

Trivia of the Week

I’ve made a career in writing for over 14 years, but only two pieces of writing I did ever went viral. Both were Agatha Christie trivia, shared on Instagram!

One of these was about Christie’s training and work experience as a pharmacist’s assistant. Christie knew all about real poisons and used them liberally in her novels, describing their action, symptoms, and effects with great accuracy. Her contemporaries would either not name their poisons, create fictitious ones, or simply choose a different murder weapon.

During Christie’s time, these poisons were far more accessible than now—often found in common medicines. Many of them could also be (and indeed, were) synthesised from plants if you had the right laboratory equipment. Christie’s job at the pharmacy involved actually making up these medicines in the exact doses—they were not mass-produced and pre-packaged like today.

What’s interesting is that if you go to Torquay in Devon, where Christie was born, you can visit a poison garden inspired by her works. Part of the grounds of Torre Abbey, this garden was created by head gardener Ali Marshall, to house a number of sinister plants mentioned in Christie’s works, including the sources of digitalin, ricin, cyanide, and morphine. You can also admire a number of benign plants featured in her books.

Here’s a puzzle for you. There’s a highly poisonous plant that grows wild in India whose beautiful flowers are used to worship the god Shiva. It’s mentioned in a number of western detective novels, including an Agatha Christie. Do you know its name?

I was born and raised in Kerala, where surnames are often our fathers’ or mothers’ first names and sometimes, simply their initials. When I quote women, I often wonder if I should use their first name instead of a handed-down surname. I myself prefer to be quoted by my full name OR my first name. In this case, Ngaio is more fun to write (and say out loud in my head). From all accounts, Ngaio danced to the beat of her own drum; so I hope this has her blessings.

I should probably call this an issue but I like the idea of naming my newsletters the way TV shows are named—with series and episode numbers. So, episode it is.

Aiyyo, for anyone who’s not a South Indian, is the equivalent of “Oh, no.”

Really interesting to read your thoughts here. The Ngaio Marsh books I've read I've normally given a rating of 3/5.