On October 2nd, Gandhi Jayanti, I sat in a cafe writing the first draft of this essay. It felt odd to write about murder on the birthday of a man renowned as an advocate of non-violence. Because, of course, murder is violent.

Violence. Does the word conjure up images of blood and bloated corpses? Physical assault and gratuitous gore? You will find very little of this in the works of Agatha Christie, which gives rise to the impression that she is a writer of non-violent mysteries.

In this, the eighth episode1 of About Murder, She Wrote, I want to dispel that myth. There is plenty of violence in Christie, if you know where to look.

Defining violence

The simplest definitions of violence are “behaviour causing harm by the use of force” (Oxford) or “actions that are intended or likely to hurt people or cause damage” (Cambridge). Physical assault is only one way to commit violence. Where Agatha Christie shines is the other kind that causes just as much damage—emotional violence.

While physical violence can sometimes be impersonal—interrupted burglars killing a home owner, a gunman spraying bullets in a college, a drunken brawl—emotional violence is always committed when there is a close relationship and a power imbalance between the parties. One person in the relationship feels powerless (victim) and at the mercy of the other. The other person (perpetrator) enjoys using their power to either wilfully or subconsciously control the victim.

Emotional violence can take many forms: expressive aggression (verbal abuse, humiliation, degrading someone publicly or otherwise), threats, gaslighting (manipulating someone so that they start questioning their own thoughts, beliefs and perception of reality), exploitation of vulnerabilities, and coercive control (by isolating someone, controlling their freedom, cutting off access to money, dictating their choices of clothing or behaviour, extreme criticism etc.)

A powerful example of emotional violence in Christie’s works is Appointment With Death, in which she sketches one of her most vile characters: Mrs. Boynton. Once a prison warden, she is a woman who wields an incredible level of control over her daughter and step-children. She has managed to break their spirit and self-worth so much that they become puppets doing her bidding. They—grown adults with no physical restraints—continue to live under her spell, make no friends, never travel or go out to work, and suffer in silence as she takes away every bit of hope and opportunity from their lives.

To understand Mrs. Boynton, you must read the book—the 2008 adaptation is awful and one of the many, many missteps it makes is to show Mrs. Boynton physically abusing her children. The whole point of Christie’s original work is that she didn’t need to—her control was absolute without the slightest need for physical brutality.

Mrs. Boynton is not the only parent from hell that Christie wrote. If she wielded control through psychological tactics, Simeon Lee, the rich patriarch in Hercule Poirot’s Christmas (a meh title for a fantastic book) also controls the purse strings. He is said to have cheated on his wife, humiliated and bullied her to death, and continues to do the same with his children. He belittles them, is disdainful of their potential, and threatens to cut off their allowance and alter his will to keep them under control. The impression you form is of children trapped in adult bodies, desperately trying to please Father.

These are examples of overt emotional violence—the reader knows that these characters are nasty and sadistic. But emotional abuse can also be carried out in stealth mode—a fantastic example is Towards Zero. In this book, one person is systematically gaslighted into a sort of emotional paralysis. They suspect that they are being manipulated and framed but are unable to react to save themselves. It takes Superintendent Battle and a complete stranger to swoop in and save the day.

Gaslighters often take the form of chronic invalids in Christie’s works, exaggerating their health condition (or sometimes, faking it entirely) to get their loved ones to do their bidding. The manipulative Edith Wetherby in Mrs. McGinty’s Dead who pretends to be weak and ill to keep her daughter chained to her bedside, the demanding Timothy Abernethie in After the Funeral who gets his wife to do everything from cooking and cleaning to car repairs while he frets in his armchair, and the scheming hypochondriac Barbara Franklin in Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case who uses her illness to keep her husband’s loyalty, are all examples.

At first read, these characters may appear to be merely difficult, not violent. But the extent of emotional damage they have caused becomes apparent when you observe how their victims behave. They become compliant to the point of absurdity. No demand is seen as unreasonable. They bend over backwards to please the perpetrator and justify them to others. When something disrupts the preferred routine of the perp’s life, the victims show signs of anxiety because subconsciously, they know they will be blamed.

Sometimes, even after the death of the perpetrator, the victims struggle to come out of their locus of control. For instance, James Bentley, the prime accused in Mrs. McGinty’s Dead, constantly references his long-dead mother’s views and preferences, and tries to live a life she would have approved of.

The characters I have cited so far were all emotional abusers who knew what they were doing. Christie has also written quite a few characters whose behaviour caused terrible harm to those under their influence—but of which they were completely unaware. The saddest example is Marina Gregg, the movie star protagonist of The Mirror Crack’d From Side To Side. Desperate to be a mother, she adopted three or four children and showered them with affection, only to cast them aside upon discovering that she was pregnant. Needless to say, she leaves a trail of tears behind.

Rachel Argyll from Ordeal By Innocence is another matriarchal figure who adopts five children from underprivileged families and becomes feverishly obsessed with them, trying to arrange every aspect of their lives. The result is that they all grow up to be maladjusted, unhappy adults.

So did Christie never write physical violence?

Of course, she did. Several of her murders are pretty brutal—a young girl is battered beyond recognition in Nemesis; a kind, loyal woman is tricked into drinking hydrochloric acid in Murder In Mesopotamia; a harmless widow is hacked to death with a hatchet in After The Funeral; an old man’s throat is slit in Hercule Poirot’s Christmas… I could go on.

Agatha Christie chose not to describe the state of a rotting body or the number and shape of wounds or the jubilation/high felt by the murderer as so many modern novels do. But she never shied away from the ugly, violent side of murder. In fact, her heart was firmly with the victim. In her autobiography, she writes movingly about the pain and fear felt by unassuming victims in their last moments and staunchly advocates for capital punishment for murderers.

Some of Christie’s emotional abusers are also the murderers or the masterminds behind the murders (I haven’t named any of them because…spoilers.) All of them are gratifyingly outed by the end of the books. But what about those who are merely nasty pieces of work? It is harder to prescribe a fitting punishment for them.

Christie had an immensely satisfying workaround here too—a number of her perpetrators of emotional violence end up getting murdered.

Were they killed by their victims or someone else entirely? You’ll have to read the books to find out. :)

Book of the Week

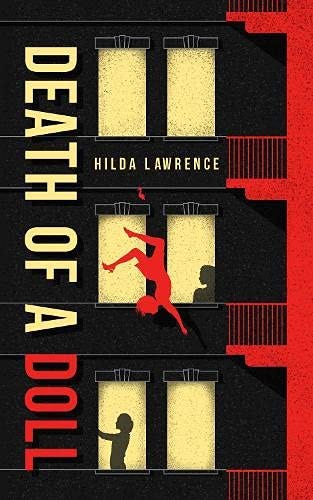

Plain, mousy Ruth Miller works at an upmarket department store and has just bagged a spot at Hope House, a nice hostel for working girls. She arrives, eager to start a new life with good company and a shorter commute, only to be horror-struck at what she finds. A day later, at the end of a dance party evening where every girl is dressed in identical doll costumes (complete with mask), one of them falls to her death. What the hell is going on?

DEATH OF A DOLL by Hilda Lawrence

American mystery writer Hilda Lawrence (1906-1976) wrote only five books and by all accounts, Death of A Doll (1947) is her best. In any case, it’s the only one of her works that I’ve read and I thoroughly recommend it. Set in a hostel for working women in Manhattan, New York, it has the feel of of an Alfred Hitchcock movie: scene—scene—scene—scream! Apart from the suspense and thrills, there’s a fantastic bit of clueing that’s as dextrous as an Agatha Christie trick. If you know me, you know that this is the highest praise I can bestow.

Rating: 🩸🩸🩸🩸💧

Trivia of the Week

Poison is not the most popular murder method for mystery writers because it needs a lot of background research. What is the right way to administer it? What dosage would be fatal? How quickly does it take effect? It’s way easier to choose stabbing or shooting or a blow to the head with a blunt instrument.

One of Agatha Christie’s (many) claims to fame is her use of real poisons in her novels. Morphine, arsenic, coniine, digitalin, cyanide, aconite…she’s used them all. Her knowledge of poisons is no accident—she trained as a pharmacist’s assistant during WWI and passed exams to qualify as a medical dispenser. At the time, medicines did not come prepackaged in the right doses. They had to be mixed according to prescription and provided individually to patients. So she had an almost encyclopaedic knowledge of toxins.

But that’s not the interesting part—thanks to her works, a notorious poisoner was apprehended by the police in 1971.

Graham Frederick Young was fascinated with chemistry since childhood—unfortunately, he did not confine his experiments to a lab. As a teenager, he tested various poisons on his family members and classmates, eventually killing his stepmother. When suspicion fell on him, he underwent psychological evaluations, which revealed a high IQ but zero empathy. He was sent to a psychiatric hospital where he seems to have continued his chemistry studies.

Upon release nine years later, he joined John Hadland Laboratories in Hertfordshire, where nobody knew of his criminal past. Soon, his colleagues began to fall mysteriously ill, complaining of hair loss and severe stomach cramps. Two of them died from the poisoning and the police got involved.

One of the doctors assisting Scotland Yard with the investigation recognised the symptoms of thallium poisoning, thanks to an Agatha Christie novel2 he was reading in which she had described its effects in accurate detail. Media at the time speculated that the same book had inspired Young to use thallium—but when asked directly, he denied ever having read the book.

Christie’s description of thallium poisoning has actually saved a couple of lives. In 1975, the author got a letter from a woman in South America who thanked her for describing thallium poisoning. Apparently, it had helped her save the life of a friend who, the woman claimed, was being poisoned by his wife.

She wrote: "Of this I am quite, quite certain - had I not read [your book] and thus learned of the effects of thallium poisoning, X would not have survived; it was only the prompt medication which saved him; and the doctors even if he had gone to hospital, would not have known in time what the trouble was." Source

Two years later, a baby girl was brought to Hammersmith Hospital in London, gravely ill. Even after blood tests and lumbar punctures and X-rays and EEGs, the doctors couldn’t figure out what was wrong with her. Until Marsha Maitland, a hospital nurse, overheard them discussing the symptoms and offered a suggestion: could it be thallium poisoning? She had just read Agatha Christie’s book herself.

Dear reader—it was thallium.

The child had gotten her hands on some insecticide stored under the sink. Thanks to Nurse Maitland—and Dame Christie—she was saved! If you’re interested in the full story, listen to this episode of chemistry podcast The Episodic Table of Elements.

I should probably call this an issue but I like the idea of naming my newsletters the way TV shows are named—with series and episode numbers. So, episode it is.

I didn’t mention the name of the book since it is a mild spoiler. For those who really want to know, here’s the name: Wkh Sdoh Kruvh. I’ve used the Caesar cipher shifted by 3. Use this tool to decode.

It is quite remarkable that Dame AC made use of Munchausen's Syndrome so effectively even before it had become part of common medical lexicon. (Wiki note: despite empirical evidence that docs were aware of, this condition itself was largely unnamed until 1951). And the subtlety of her violence makes it even starker, giving us the template for the most villainous villains whose infamy lies in their ability to manipulate instead of ranting and screaming.

Good read, this!