This essay is part of a collaborative, constrained-writing challenge undertaken by some members of the Bangalore Substack Writers Group. This month, each of us examined the concept of ‘LANGUAGE’. At the bottom of this snippet, you’ll find links to other essays by fellow writers.

Agatha Christie might be the most popular mystery writer of all time—but rarely is she praised for her prose. Compared to the literary flourishes of Dorothy L. Sayers or the witticisms of Ngaio Marsh, Christie’s writing is rather plain. However, she has used the rules and conventions of the English language to aid and abet her own strengths—ingenious plotting and clever clueing. Here is a spoiler-free look at some examples.

Language as Object

Christie knew that how something is written—capitalisation, punctuation, formatting, and so on—can be just as telling as what the words say. In linguistics, this is called orthography: the systems governing how a language is written.

In one of her novels1, a young woman dies by poisoning. To avoid spoilers, let’s say the poison is ‘ethanol’. A tube of ‘ethanol’ has gone missing from the local district nurse’s stock. And at the scene of the crime, a part of a medicine label with the name of the poison is discovered.

All this points to a particular person as the culprit and they are arrested. But when Hercule Poirot is roped in to discover the truth, he observes an orthographic anomaly: if the paper is from the printed medicine label, why doesn’t it say ‘Ethanol’ with a capital E?

The answer to this question becomes an important clue about the true nature of the murder.

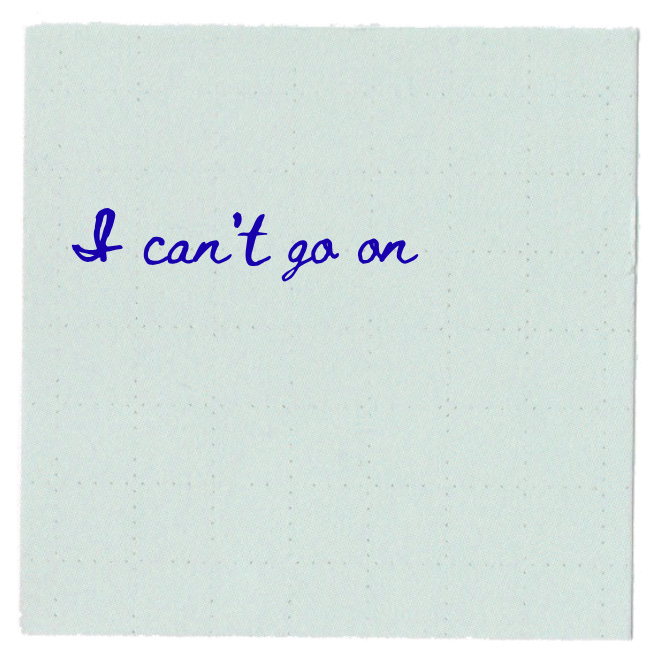

Another of my favourites is from The Moving Finger. Residents of the idyllic village of Lymstock are plagued by poison pen letters. After receiving a particularly cruel letter, a respectable middle-aged woman has apparently killed herself. Her suicide note reads “I can’t go on”.

While the police investigate who wrote the letters and the villagers gossip about the contents, Miss Marple notices an orthographic anomaly in the suicide note: where is the full-stop?

This prompts more questions. Why is the suicide note written on a bit of notepaper? Why isn't it addressed to anyone? Important questions, because as it turns out, there is a murderer at large.

In constructing these clues, Christie treats language as a visual artefact—information is hidden in what language looks like on the page. What could be cleverer?

Language as Psychology

Christie also played with the psychology of language—how tone, silence, or emphasis can shape what we understand, or fail to.

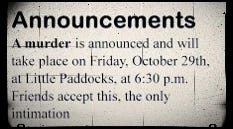

In A Murder is Announced, the villagers of Chipping Cleghorn arrive at Letitia Blacklock’s home in response to an intriguing notice in the local paper.

The lights go out. A masked man appears and shines a torch around the room. Shots are fired. When the lights come back, the man lies dead.

As the story unfolds, suspicion swirls around who shot him and who planned the gathering (Letitia Blacklock says she certainly didn’t.) Sometime later, a witness mentions something odd to a friend, “She wasn’t there.”

The friend steps away to finish a chore… and returns to find the speaker also murdered. Miss Marple is struck by the cryptic line. How was it spoken, she asks the grieving friend. Was the emphasis on she or on there?

‘She wasn’t there.’ brings the focus to a particular person, while ‘She wasn’t there.’ turns attention to a part of the room. To me, this is a classic Christie clue that zooms in on an apparently trivial point to reveal something of tremendous significance.

Tone is equally evident in intimate letters. In Five Little Pigs, Caroline Crayle is convicted of murdering her husband. Throughout the trial and in prison, she remains unusually calm. In a letter to her sister, she writes: “It’s all alright, my darling. It’s all alright.” She doesn’t protest her innocence or confess her guilt. But before she dies, she leaves a letter to be delivered to her daughter Carla on her 21st birthday. In it, Caroline writes that she is innocent. To discover the truth, Carla turns to Hercule Poirot.

In this beautifully layered story of murder in retrospect, Poirot studies the tone of Caroline’s letters. What was she reassuring her family about? How could she sound so at peace if she was wrongly accused? We never meet Caroline directly—only through the remembered fragments and distorted memories of her loved ones. But it’s her words, and how she uses them, that offer clues to who she really was.

If this novel plays with truth filtered through others, Christie also wrote stories that let us into the mind of the killer2. You might read their own thoughts and words and never suspect the truth. The biggest delight in re-reading these books is discovering Christie’s sleights of language through omission and commission.

Language as Culture

And then there are the clues Christie hid within the quirks of idiom, children’s rhymes, or literary references.

In Why Didn't They Ask Evans, you need to know how people of different social classes were addressed in pre-war Britain to guess the identity of the titular Evans. This is more of a thriller than a classic puzzle mystery, and Christie doesn’t quite play fair—but if you’ve watched enough Downton Abbey, you’ll appreciate the trick. 😀

Some of her obscure idiomatic clues are near-impossible for modern readers to decipher. In The Tuesday Night Club, the police find the phrase “hundreds and thousands” imprinted on a letter pad and assume the husband killed his wife for a fortune. Only Miss Marple, with her Victorian domestic sensibilities, realises the phrase refers to coloured sugar sprinkles! It’s probably for the best that Poirot doesn’t appear in these stories—his English is better than he lets on, but unlikely to stretch to regional culinary colloquialisms.

Children’s rhymes appear often in Christie’s works, as book titles and plot devices. Some references, like And Then There Were None, are chillingly effective. Others, like One, Two, Buckle My Shoe or Hickory Dickory Dock, feel ridiculous forced. In many stories, she also draws on Shakespeare, the Bible, Jacobean tragedies, and even the masked stock characters of commedia dell’arte (16th century Italian improv theatre).

Agatha Christie has expressed regret about never having had a formal education (she was homeschooled and never went to college). But looking at the many inventive ways in which she played with language, I don’t think she missed out on much.

You can read what my fellow Bangalore Substackers have done with the prompt ‘LANGUAGE’. Some lovely themes explored here.

Geography & Language by Devayani Khare, Geosophy

Poetic Silence - From Anand Bhavan to 3039 and back by Amit Charles, @acnotes

Of Language, Love and Longing: Politics, Mother Tongue and Loss by Aryan Kavan Gowda, Wonderings of a Wanderer

In search of my lost mother tongue by Siddhesh Raut, Shana, Ded Shana

I’ve been thinking a lot about tongues, again. by Ameya, (Always) Ameya

The Bengaluru Blend by Avinash Shenoy, Off the walls

Loss of a language By Rakhi Anil, Rakhi’s Substack

The language question by Rahul Singh, Mehfil

The Dance of Languages by Haridas Jayakumar, Harry

No Garam Aloo in Tamil Nadu by Ayush, Ayush's Substack

Lost in translation by Vikram, Vikram’s Substack

The Language Beneath Words by Mihir Chate, Mihir's Substack

What does this mean? by Nidhishree Venugopal, General in her Labyrinth

I have no words by Richa Vadini Singh, Here’s What I Think

Jal-Elephants, Thread-Navels, and Other Sanskrit Beasts by Rajat Gururaj, I came, I saw, I Floundered

An Ode to Languages, by Lavina G, The Nexus Terrain

Beyond Words and Dialects by Aarti Krishnakumar, Aarti’s Substack

If I may suggest another versatile author, Joanne Harris — better known for her tantalising chocolate-themed novels. Her Gentlemen and Players is a psychological thriller, with murder in a backdrop. Brilliant use of language and logic to trap the reader!

Thanks for another interesting post! I think the straightforwardness of Christie's prose makes it even more satisfying to be fooled by her with these kinds of verbal misdirections - everything is clear, if only you knew where to look!

On your "hundreds and thousands" example - it's still very common in the UK to refer to these sprinkles (eg for cake decoration) as hundreds and thousands. I didn't realise this would be obscure to other readers!