S01E03: Locked rooms, closed circles & impossible crimes

These are not the same but even ChatGPT doesn't seem to know the difference.

The other day, I overheard someone at Blossoms confidently telling their friend that (a) Agatha Christie is the best and (b) she specialises in locked room mysteries.

I have to admit I was torn.

On the one hand, I wholeheartedly agree that Agatha Christie is the best (all hail the queen!) and wanted to shake this young person by the hand for their good taste. On the other, I was seeing red because Agatha Christie has written only a handful of locked room mysteries and I wanted to give this person a good shaking for smugly spreading misinformation. (I didn't, I don't want to be banned from Blossoms.)

What Christie specialises in are closed circle crimes. They are different from locked room mysteries, which are related to impossible crimes but not the same. And it struck me that not all readers understand the difference. In this, the third episode1 of About Murder, She Wrote, allow me to geek out about the topic.

Closed Circle Mysteries

These are mysteries in which the suspects are limited to a small, defined group. Let me give you examples from Christie's works.

And Then There Were None - Ten people are brought to an isolated island off the Devon coast by the mysterious U. N. Owen and they start dying off one by one. Because the island is cut off from the mainland, the murderer has to be one of them.

Death on the Nile - Here, the circle is wider. There are seventeen passengers on the steamer Karnak all set to tour the Nile river. One of them is Hercule Poirot the detective and one of them will soon be the victim, which limits the suspect circle to fifteen passengers.

Death in the Clouds - The circle consists of the passengers in an aeroplane, flying from Paris to London—and one of them ends up dead.

In all these examples, the crime scene is somewhat physically removed or separated from the rest of the world. But that doesn't need to be the case always. A closed circle crime could also happen during a house party or in a hospital. The key point is that only a limited number of people have access to the crime scene.

They will all be introduced to the reader early in the book. Many of them will have at least one of the three—motive, means, and opportunity—to commit the murder. The detective's job is to figure out who among them is the killer. This is fun for the reader because on page 274, you won't suddenly be told that all the suspects you've been scrutinising so carefully are innocent and the murderer is a random madman who climbed in through the window.

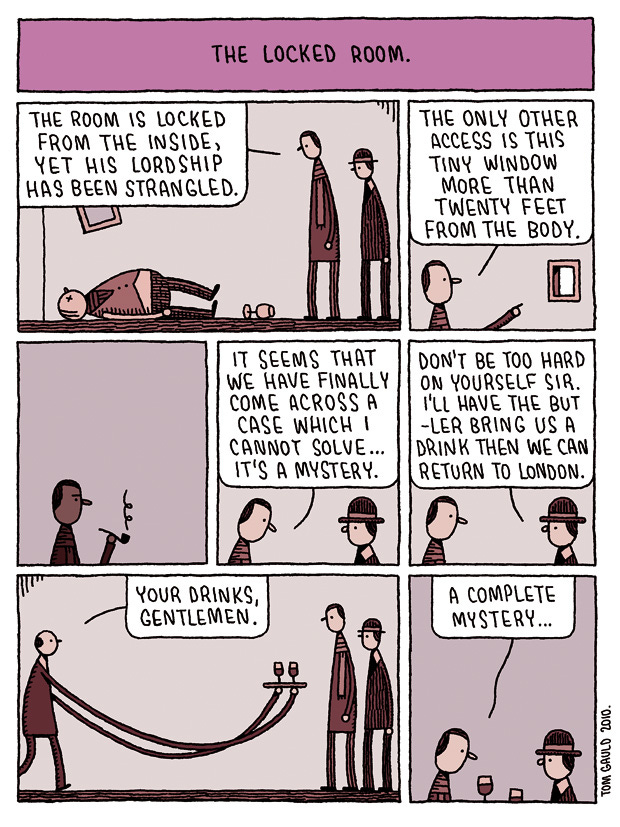

Locked Room Mysteries

Locked room mysteries often literally mean that. A crime (usually murder or theft) happens inside a locked room/tower/other location. If there's a dead body, it will look like a suicide as nobody could have entered or left the space without being spotted. Yet, it cannot be suicide (otherwise, where's the story?) The detective's job here is more focused on the how and the who is sometimes almost incidental.

If you enjoy puzzles, you will particularly enjoy these type of mysteries. Sometimes, the solutions are incredibly simple but non-obvious and sometimes, they are just...incredible. The master of this sub-genre is John Dickson Carr who also wrote under the name Carter Dickson. Here are three of his most renowned locked room mysteries.

He Who Whispers - A man goes up a tower. Fifteen minutes later, he is found stabbed to death with the murder weapon lying next to his body. The tower has only one staircase and a family picnicking nearby swear that no one went up or down it during this time. So who killed him and how did they leave undetected?

The Hollow Man - Witnesses see a masked figure enter the room of Professor Grimaud and slam the door. They hear a gunshot. When they break open the door lock, Grimaud is bleeding to death but there's no one else in the room.

The White Priory Murders - A Hollywood actress in England for a shoot is beaten to death in a pavilion. It's winter, snow's been falling, and only one set of footprints can be seen going towards the pavilion. There are none leading away from it. Where did the murderer disappear?

In case you're wondering, Agatha Christie wrote only two legitimate locked room novels—Murder in Mesopotamia and Hercule Poirot's Christmas. I love both but the twist in the latter is spectacular.

Impossible Crimes

All locked room mysteries are impossible crimes but not all impossible crimes are locked room mysteries. Which is a very CAT-exam way of saying that impossible crimes are a superset of locked room mysteries. These are crimes that are seemingly impossible, yet have actually happened under circumstances that seem unexplainable...until the author (via the detective) explains it.

Impossible crimes take the puzzle element and stretch it like mozzarella on a pizza slice. So much so that sometimes, the final explanation may sound possible but not very plausible. That said, they're still a great deal of fun. Here are some recommendations.

Pick up any of the literally hundreds of impossible crime short stories written by Edward D. Hoch, for clever and surprisingly realistic solutions. Most of his stories feature country GP Dr.Sam Hawthorne or the police detective Captain Leopold as the sleuths—both likeable characters, although the good doctor is more memorable. Hoch's stories have been turned into some radio plays and enacted e-books too, which make for fun listening.

Inherit the Stars by James P. Hogan (1977) - I haven't read this one but it sounds brilliant and gets a lot of love from impossible crime enthusiasts who love the blend of sci-fi and mystery. The premise is this—humans find a man on the moon, but he is wearing a red spacesuit, very much dead, and about 50,000 years old. How could this be possible?

Book of the Week

Death Comes As The End (1944)

It is Egypt, 2000 B.C., where death gives meaning to life. At the foot of a cliff lies the broken, twisted body of Nofret, concubine to a Ka-priest. Young, beautiful and venomous, most agree that she deserved to die like a snake. Yet Renisenb, the priest’s daughter, believes that the woman’s death was not fate, but murder. Increasingly, she becomes convinced that the source of evil lurks within her own father’s household.

Didn’t the title give you goosebumps? This is a criminally underrated Agatha Christie and has many ‘only’s to its credit.

It’s the only historical mystery written by Christie. Her works are usually contemporaneous to her times, which is the 20th century. But this one is set seriously far back—in Thebes, Ancient Egypt in 2000 B.C. Christie was married to the British archaeologist Sir Max Mallowan and for a good part of her life, accompanied him on his digs in Iraq and Syria. She loved the middle-east and the prospect of getting glimpses of the people who had once lived and walked those lands through the archaeological remains that survived. She was a working member of the team, spending hours each day cleaning and piecing together the pottery and remnants they dug up. She was also the official photographer and had her own dark room to develop the pictures of their finds. If you’re interested in this side of her life, you should read her light-hearted archaeological memoir ‘Come, Tell Me How You Live’.

It is one of only four Christie novels to never have been adapted on screen—TV or cinema. The other 60+ novels and numerous short stories have all been adapted, some multiple times. Not that I want Kenneth Branagh to come swooping in and destroy one more of my favourites, but I’d love to see this on the big screen. The sets alone would be incredible.

It is the only time she let someone else persuade her to change the original ending she’d intended for the book. You see, the idea for this book was suggested to her by family friend Stephen Glanville, a noted Egyptologist. In a conversation with him, she became convinced that be it 2000 B.C. or 1944, people were essentially the same—their desires, emotions, fears, resentments. Glanville not only convinced her to write the book but helped her a good deal with the research needed to make it authentic to the setting. After she’d finished the book, he argued for a different ending and she allowed herself to be persuaded. In her autobiography, she writes that she regretted this decision and should have stuck to her original ending. Alas, no one knows what she had in mind. I would kill to know!

Rating: 🩸🩸🩸🩸🩸

Trivia of the Week

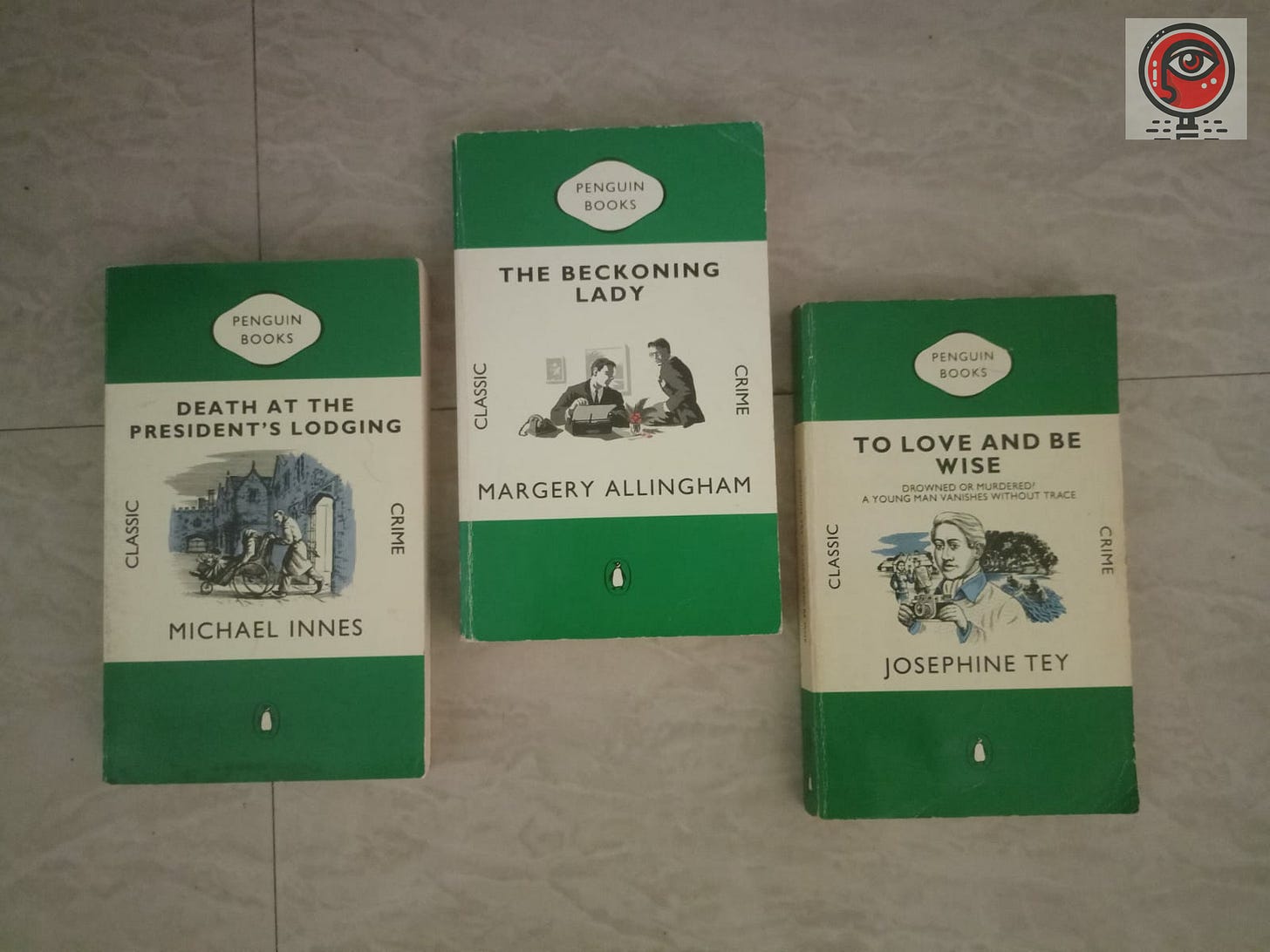

If you are in a bookshop and in the mood to pick a crime novel but don’t want to read the latest bestsellers or search Goodreads, here is a simple hack—look for the Green Penguins.

On his way back from visiting Agatha Christie at her Devon home, the struggling publisher Allen Lane found himself stuck at Exeter station without a book in hand. Looking around the bookstalls at the station, he noticed that readers had just three options.

Magazines and newspapers.

Fine, bulky hardback editions that cost at least 7 shillings (approx. £20 today), purchased mostly by the educated elite or by libraries.

Cheaply produced trashy literature, the descendants of ‘penny dreadfuls’ from the 19th century.

Just a few months ago, Lane had attended a conference about ‘The New Reading Public’ which talked about how the post-WWI middle class had more leisure, spending money, and interest in reading than the generations that had come before. Lane put two and two together and made an excellent decision—to publish good quality, affordable books for the new reading public.

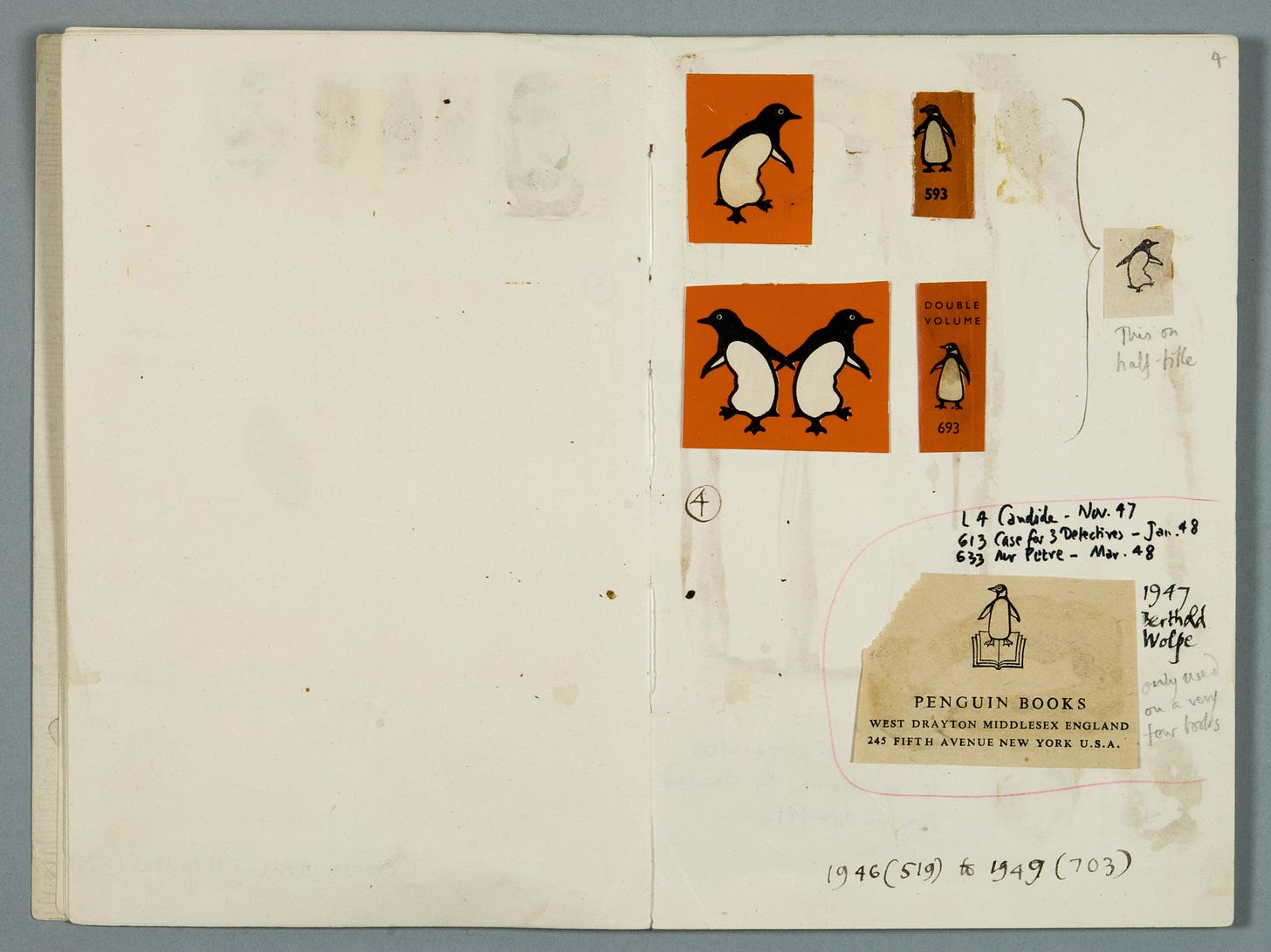

He made some excellent branding choices which led to the success of the venture. The first was to create an icon that was ‘dignified, but flippant’. His secretary Joan Coles suggested the penguin and an illustrator was sent to the London Zoo to watch and draw some penguins!

His second smart decision was to move away from the gaudy illustrated covers of the time and colour-code the books. This way, readers could quickly pick what they wanted—orange for Fiction, blue for Biography and green for Crime. Later, this was expanded to add purple for Essays & Letters and cerise for Travel & Adventure books.

This colour coding was a brilliant branding tactic because it helped the publisher market a series or genre rather than an individual author. A commuter in a hurry could quickly pick the latest green or orange Penguin from a station bookstall and know roughly what to expect even if they didn’t know who the author was. At the time, The Bodley Head publishing house that Lane had inherited from his uncle was struggling and could not afford the advances commanded by the bestselling authors of the time. By branding the series, Lane diverted the spotlight back to the publisher.

Lane also made some smart pricing and distribution choices, all of which are explained in detail in this excellent episode of mystery podcast Shedunnit by Caroline Crampton.

If you, like me, haunt secondhand bookstores, you now know what the Penguin modern classics book covers mean. Happy browsing!

In case you missed last week’s episode, you can read it here. In it, I explore the many roles played by the Watson, that essential sidekick great detectives seem to need.

See you next week with another essay, recommendations and trivia. 👋🏼

I should probably call this an issue but I like the idea of naming my newsletters the way TV shows are named—with series and episode numbers. So, episode it is.

This is my favourite episode so far! All the recommendations are gold. How fun!

Wonderful write up Gowri! I remember reading my first Agatha Christie while in school and since then I have been hooked! I love the genre of whodunit , murder mystery and crime fiction! One of the best that comes to my mind is "The Purloined Letter"! Though not a full blown book but short story which actually made me delve deeper into such fiction and till today I love reading those! Keep the series coming ! You are a wonderful writer who dives deep into the subject with easy enough explanations for a layman to understand!