S01E01: Murder, they read. But why?

Examining the question: Why are people interested in something as dark as murder mysteries?

It is Sunday afternoon, preferably before the war. The wife is already asleep in the armchair, and the children have been sent out for a nice long walk. You put your feet up on the sofa, settle your spectacles on your nose, and open the News of the World. Roast beef and Yorkshire, or roast pork and apple sauce, followed up by a suet pudding and driven home, as it were, by a cup of mahogany-brown tea, have put you in just the right mood. Your pipe is drawing sweetly, the sofa cushions are soft underneath you, the fire is well alight. The air is warm and stagnant. In these blissful circumstances, what is it you want to read about?

Naturally, about a murder…

George Orwell in his 1946 essay ‘The Decline of the English Murder’

When I ran a poll last week asking if anyone would want to read a weekly newsletter about murder mysteries, I got a surprising number of yays. My favourite response is this one.

But I also got quite a few of the other kind. A relative asked me if I am doing okay. An old friend joked that my husband should be worried. A friend, genuinely puzzled, asked me why anyone would want to read about murders.

That’s a great question. One that I think is worth exploring in this, the debut episode1 of About Murder, She Wrote.

If you are a fan of the genre, think about it for a moment. When you have had a crazy week and want something to take your mind off the demands of work and life admin, why do you pick up a murder mystery? A book in which at least one person is killed and at least two more are likely to be coshed over the head or nearly run over by a car? What’s relaxing about that?

You and I are in august company though. Several Presidents of the United States, Queen Elizabeth II, writers including P.G. Wodehouse and Ruskin Bond, poets T.S. Eliot, W.H.Auden and Cecil Day-Lewis, filmmakers Satyajit Ray and Vishal Bharadwaj, and countless other luminaries have publicly declared their love for detective fiction, which, in 90% of cases, revolves around murder.

Exercise for the Little Grey Cells

In a scathing 1945 essay about the genre, American literary critic Edmund Wilson writes, “…the reading of detective stories is simply a kind of vice that, for silliness and minor harmfulness, ranks somewhere between crossword puzzles and smoking.” He meant it as an insult but I think he actually hit the nail on the head.

The biggest appeal of murder mysteries—especially the classically structured kind that have a dead body, a limited number of possible suspects, clues hidden within the text, and a detective on the scene questioning people and putting the pieces together to finally reveal “whodunit”—is that they feel like a game. Not as intellectually taxing as something like chess but also not a mindless game of chance.

As a reader, you get to pit your wits against the detective’s and see if you can spot the murderer before (s)he does. In fact, this was a staple feature of the early Ellery Queen mystery novels from the 1930s. Near the end of the book, Queen (the fictional detective and also the pen-name of the authors of the series) would address the reader directly and tell them that they now had all the clues necessary to solve the mystery. This ‘Challenge to the Reader’ was incredibly popular and when the series was turned into a radio series in the 1940s, each episode featured a panel of armchair detectives, including celebrities, who were invited to try and solve the mystery on air.

It is safe to say that if you like puzzle-format games, you have a reasonably good shot at enjoying classic detective fiction.

Neat Little Endings

We live in the real world where we have little control over what happens. We make decisions and put in effort without knowing how things will eventually pan out. There are too many variables to predict anything with certainty and no outcomes are guaranteed.

In a world like this, murder mystery novels are little oases of sanity. They have creative settings but with clear limits. The murderer is one of a set of people who have all been introduced to you. There are only a limited number of possibilities to explain what happened. And by the time you get to the last chapter, you know that along with all the characters rounded up in the library, you too are going to be given all the answers—who, why, when, and how.

Sweet closure, sometimes with a satisfying delivery of justice. That’s more than enough reason to escape into the pages of a murder mystery.

Glimpses into the Human Psyche

What would drive one human to kill another? What intensity of emotion, what greed or rage or resentment or sense of injustice, could make someone take that drastic step? The more you read/watch the genre, the more you realise that they are about the human psyche—both individual and collective.

Isolation and mental health, disillusionment with the justice system, the complex dynamics within a family, the expectations or pressure from society, cultural conditioning (more visible in detective fiction originating outside the West, particularly Japan and India)…a whole gamut of situations are covered in these books. And long after you put down one of them, you may find yourself reflecting on the characters and wondering how you would have reacted in their shoes.

You may not find this depth and range in every book you read but it is still the question the finest murder mysteries centre around.

An Arm’s Length from Reality

If my previous point was about the realism in detective fiction, I’m going to slightly contradict myself and talk about how this genre is also somewhat removed from reality.

Have you noticed that there’s very little overlap between true crime lovers and murder mystery fans? Rarely will you find people who are equally enthusiastic about both. A true crime fan might pick up the odd cozy mystery during a holiday or a murder mystery fan flipping through Netflix on a Friday evening might end up watching an episode of Conversations with a Killer. But the two are different genres and, as far as I have seen, attract different kinds of people.

True crime gets uncomfortably close to real life. The victims are real people. All too often, there’s no satisfactory resolution. Compare that to fictional murders.

They are set in exotic locations—a billionaire’s private island in Greece or a luxury yacht on the Nile. Sometimes, they are set in a whole other time period or have your favourite celebrities playing detective—for instance, Queen Elizabeth II plays sleuth in S.J.Bennett’s surprisingly fun The Queen Investigates series while Jane Austen investigates crimes in Stephanie Barron’s 15-book series (I haven’t read this one).

They feature the most ludicrous incredible murder weapons—my favourite is from an episode of the long-running detective series Midsomer Murders, in which a dairy worker is crushed to death by a giant wheel of cheese!

Thus, detective fiction occupies an interesting space between reality and fantasy. The characters, their motivations, their psychological makeup are close enough to real life but at the same time, you are stepping inside a fantasy world where you have to suspend some bit of rational thinking for maximum enjoyment.

If you’re ready and willing to do that, I can promise you a whole world of possibilities and sub-genres, settings, authors, and series to explore. Take it from someone who has read over 500 detective fiction novels/anthologies and watched hundreds of hours of the same genre on TV. (Yes, I do have a job and an active personal life, why do you ask?)

Book of the Week

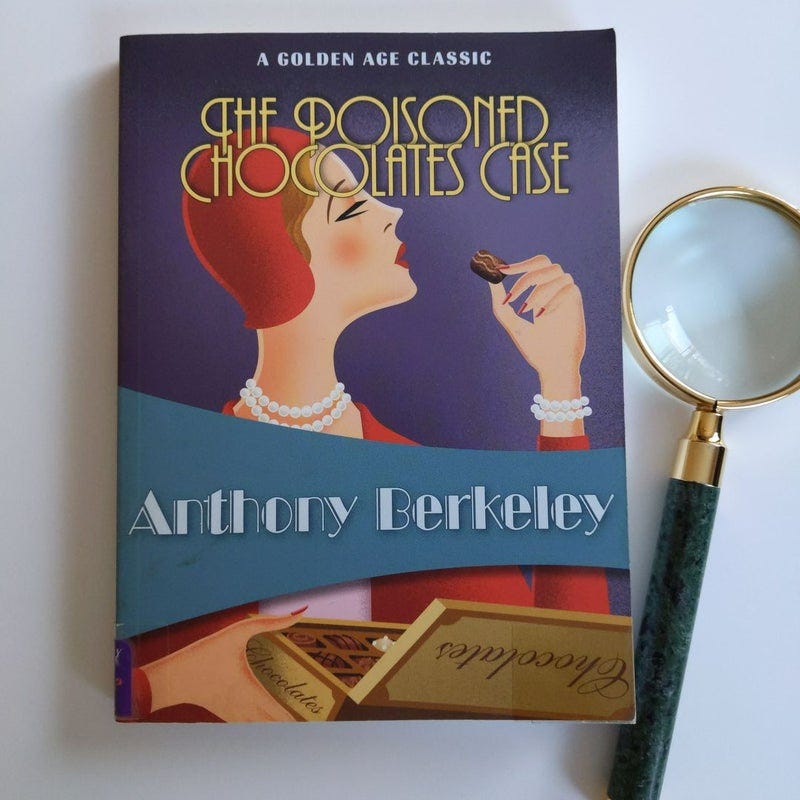

The Poisoned Chocolates Case (1929) by Anthony Berkeley

Sir Eustace Pennefather walks into his club one morning and finds that a brand has sent him a complimentary box of chocolates. He’s not a fan of such marketing tactics and passes it on to a fellow member, who takes it home. The man’s unfortunate wife eats one too many of the chocolates and dies a few hours later. Was Sir Eustace the intended victim or is there something more insidious at play?

This is a classic novel from the Golden Age of Detective fiction in which a club of amateur criminologists try to solve a murder that has temporarily stumped the police. Each of them follows their own approach to detection (deductive or inductive reasoning, actual sleuthing, psychological understanding: all included!) and proposes a solution to the case.

All the solutions are logical and clever and I love how Anthony Berkeley openly makes fun of the tropes of detective fiction. Fun to know that back in 1929, these tropes were already recognised as such. 😃

The final reveal is brilliant. The edition I read had two additional solutions—one by Christianna Brand and another by Martin Edwards, both renowned mystery writers. Personally, I prefer the way the original book ends.

Rating: 🩸🩸🩸🩸🩸

Trivia of The Week

Edgar Allen Poe is credited as the inventor of the detective fiction genre. His 1841 short story ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ is the first detective story ever written. In it, the Parisian detective C. Auguste Dupin solves the brutal murders of two women.

This was a truly pioneering work because it set the tone for many aspects of the genre—a brilliant detective, the friend who is also the narrator, the less-than-competent local police, and deduction through reasoning. You can read it for free here.

I hope you enjoyed the read. See you next week with another essay, recommendation and trivia. 👋🏼

I should probably call this an issue but I like the idea of naming my newsletters the way TV shows are named—with series and episode numbers. So, episode it is.

Hi Gowri,

It's great to read a Crime - Mystery - Thriller focused Newsletter from someone based in India. Looking forward to read more 'Episodes' and 'Series'. Till now, the only newsletters I have subscribed to are: The Agatha Christie Newsletter, Cluesletter by Mystery Manon and quite recently, Clued in Mystery by Sarah and Brook. Please let me know what Newsletters and Podcasts inspired you to Create 'About Murder, She Wrote'. :)

Really looking forward to all the recommendations! Ps: love the blood drop rating 😂